EDITOR’S NOTE: Because extended enterprise learning involves multiple disciplines, we sometimes ask other experts to share their insights with our readers. Today we feature skills development advice from Patti Shank, PhD. Patti is widely recognized as an expert in learning science and instructional design. She is the author of multiple books, including the recent “Make It Learnable” series. This post is adapted from one of those books, Practice and Feedback for Deeper Learning.

Why Practice Is Essential

When cultivating new skills, how heavily should we rely on practice? In recent years, numerous researchers have explored this question – from Anders Ericsson in Peak to Steve Rosenbaum and Jim Williams in Learning Paths. The answer is important for training professionals because it directly influences the way we design, develop, deliver and support adult learning experiences.

For example, in their analysis, Rosenbaum and Williams uncovered three practice-related workplace learning realities:

1) All too often, people who’ve completed training are actually less-than-proficient. They make costly mistakes and don’t perform at the desired level.

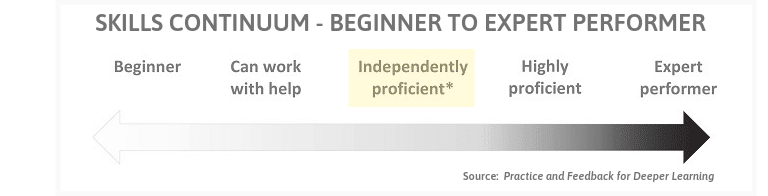

2) It takes a long time for new hires to become competent at performing core work tasks without needing much help or making many errors. This skill level is called the “independently productive” stage.

3) Training organizations can bridge this performance gap and add value by creating faster paths to independent productivity. Rosenbaum and Williams call this metric “time to proficiency.”

I would add a more fundamental observation. In my experience, too many training organizations don’t consider time to proficiency central to their purpose, so related strategies and techniques are overlooked.

Fortunately, however, learning sciences offer numerous ideas for improvement. For example, let’s look at how practice and feedback can help.

Connecting Practice with Performance

Many training researchers believe the difference between inadequate performers and independently productive performers is the right type and amount of practice. So, exactly how much practice do people need? A lot. Here are several reasons why:

- Learning happens when we’re able to connect what we already know with what we are being taught. This isn’t a simple matter.

- Human memory is slow and gets overloaded quickly. When our minds are overwhelmed, little or no additional learning can happen.

- When we’re bombarded with a lot of information in a compressed timeframe, we tend to forget most of it.

- Training methods that help people learn, maintain and remember knowledge and skills are underutilized. If you want better results, it’s important to understand and apply these techniques.

4 Keys to Effective Practice

Research tells us that the right type of practice is based on 4 characteristics:

- Specific goals

- The level of challenge must match current skills and prior knowledge

- The amount of practice is sufficient to achieve identified goals

- Appropriate feedback is part of the process

Let’s look more closely at each of these factors:

1) Is Practice Tied to Specific Goals?

Effective skills training starts with specific, measurable goals. Training goals come not from content, but from what people need to be able to do on the job.

Training that isn’t based on job context is often just a content dump. And content dumps are a poor way to teach anything.

Unless we know how people want to use knowledge and skills, we’re unlikely to develop deep learning experiences that help them apply what they learn.

2) Does the Challenge Fit Prior Knowledge and Current Skill Level?

Learning is cumulative. It builds on what we already know. What we know and what we can do serve as a foundation for learning new things.

For example, in my book, I include examples from two-factor authentication training. If you’ve never had to authenticate your identity when trying to cash a check at an online bank, or if you’ve never used computer passwords at all, you’ll have a difficult time understanding this concept.

When people have little prior knowledge of a subject, training should start at a different point and the process should be different. In this case, we should focus first on clarifying what authentication means, why it matters, how to authenticate your identity and where you might need to use it.

Stories can also help because they can illustrate the concept and related consequences. For example, “Because Calum’s mom didn’t use two-factor authentication, her Social Security payments were stolen.”

To start, build practice around some basic ideas. In this case, it could be something like this: “Where might someone expect authentication to be required? The bank? The swimming pool? The grocery store?” Work up to practicing two-factor authentication.

3) Is the Amount of Practice Sufficient?

How much practice is adequate? While analyzing the job context (the first step in this process), it’s important to figure out (usually with stakeholders) the level of skill people should have when they complete training. How much practice will help them progress to that desired level of proficiency?

In addition, what happens after initial training is over? If new skills and knowledge are rarely used or reinforced, how will people maintain proficiency? Is this an adequate level of practice?

We must realize that if people don’t immediately use what they learn, it starts to decay. And we must help stakeholders understand why it’s essential to reinforce learning over time, so people retain skills proficiency.

4) Do You Offer Appropriate Feedback?

Feedback deserves special consideration. Here is why meaningful feedback makes such a difference.

According to John Hattie – a prominent educational researcher at the University of Melbourne, Australia – feedback is one of the most powerful ways to improve learning outcomes. But interestingly, research also finds that feedback can have a negative impact! This means that those of us who design and deliver instruction must understand which factors make feedback helpful or harmful.

How Feedback Can Help Support Learning

Feedback plays multiple roles during instruction, especially related to practice. For example, feedback can help you:

- Confirm understanding when understanding is correct.

- Correct mistakes or misconceptions when understanding is incorrect.

- Close the gap between what people can do and what they should be able to do (learning objectives).

Let’s look closer at feedback factors that influence the effectiveness of feedback. This information comes largely from John Hattie, Valerie Shute (a professor of education at Florida State University) and Susanne Narciss (professor in the Department of Psychology at Technische Universität Dresden).

How Feedback Can Hurt Learning

Research has found that certain types of instructional feedback can lead to less effort and reduced learning. This includes:

- Trivial goals

- Praise

- Rewards

- Comparisons with others (such as rankings)

- Threats

- Discouragement

Multiple studies indicate that praise and rewards hinder intrinsic (internal) motivation. Therefore, it may be beneficial to avoid these techniques. Instead, instructional feedback should emphasize the benefits of learning and growth, encouraging individuals as they invest time and effort to develop knowledge and skills over time.

When people feel unsure or they make an error, feedback should help them see how to get back on track. Anxiety about the need to perform can make it harder for people to learn. Therefore, it’s important to focus on support and guidance, rather than performance at any cost.

Mapping Feedback to Prior Knowledge and Skill

The amount of skill and prior knowledge individuals bring to a learning experience greatly affect the kind of feedback we should offer. The table below lists major feedback issues in the left column. The corresponding columns to the right indicate how to handle issues at various levels on the skill and expertise continuum.

HOW TO FIT FEEDBACK TO EXISTING SKILL AND EXPERTISE

| Issues | Lower skill, less topic expertise | Higher skill, more topic expertise |

| Type of feedback | More directive | More facilitative |

| Amount of information | Specific | More detail for deeper understanding |

| Level | Task-specific | Cues, hints, details |

| Support | More support | Less support |

| Timing | Immediate | Time for mental processing |

This table offers several takeaways for instructional design professionals. First, it’s important to understand the background of training participants before instruction begins. Second, tailoring feedback to an individual situation can be useful.

That’s why the first of 5 strategies in my book is Analyze Job Context, and the first of 26 tactics is Connect Learning Objectives to Job Tasks. Job tasks can be very different for novices than for those who bring some expertise to the table. Our challenge is to anticipate and appreciate those differences and then frame learning experiences, accordingly.

Strategies and Tactics That Drive Results

The table below identifies the various strategies and tactics that I explore in more depth throughout the book, Practice And Feedback For Deeper Learning.

PRACTICE AND FEEDBACK STRATEGIES AND TACTICS

| Chapter 4 | Strategy 1: Analyze the Job Context | Tactic 1: Connect Learning Objectives to Job Tasks

Tactic 2: Analyze Conditions Under Which People Perform the Tasks Tactic 3: Evaluate What Must Be Remembered and What Can Be Looked Up Tactic 4: Analyze Social Processes Tactic 5: Find Typical Misconceptions Tactic 6: Find Out What Gets in the Way Tactic 7: Assess Support for Skills |

| Chapter 5 | Strategy 2: Practice for Self-direction | Tactic 8: Work Toward Specific, Difficult, and Attainable Goals

Tactic 9: Use Self-directed Learning Strategies |

| Chapter 6 | Strategy 3: Practice for Transfer | Tactic 10: Make Training Relevant

Tactic 11: Build Practice that Mirrors Work Tactic 12: Show the Right and Wrong Ways Tactic 13: Train How to Handle Errors Tactic 14: Include Whole-skill Practice Tactic 15: Help with Post-training Support |

| Chapter 7 | Strategy 4: Practice for Remembering | Tactic 16: Use Real Context(s)

Tactic 17: Use Self-explanations Tactic 18: Space Learning and Remembering Tactic 19: Support Memory with Memory Aids Tactic 20: Support Essential Skill Upkeep |

| Chapter 8 | Strategy 5: Give Effective Feedback | Tactic 21: Keep the Focus on Learning

Tactic 22: Tie Feedback to the Learning Objectives Tactic 23: Offer the Right Level of Information Tactic 24: Fix Misconceptions Tactic 25: Give Feedback at the Right Time Tactic 26: Structure Feedback for Ease of Use |

EDITOR’S NOTE: This post has been adapted, with permission, from articles published on the eLearning Industry blog.

Share This Post

Related Posts

The Future of Customer Education: Customer Ed Nugget 16

Customer education is rapidly evolving as organizations embrace new strategies and tech. What does this mean for the future of customer education? See what experts say on this Customer Ed Nuggets episode

Education Strategy Mistakes to Avoid: Customer Ed Nugget 15

What does it take to deliver a successful customer education program? It starts with a solid education strategy. Learn how to avoid common pitfalls on this Customer Ed Nuggets episode

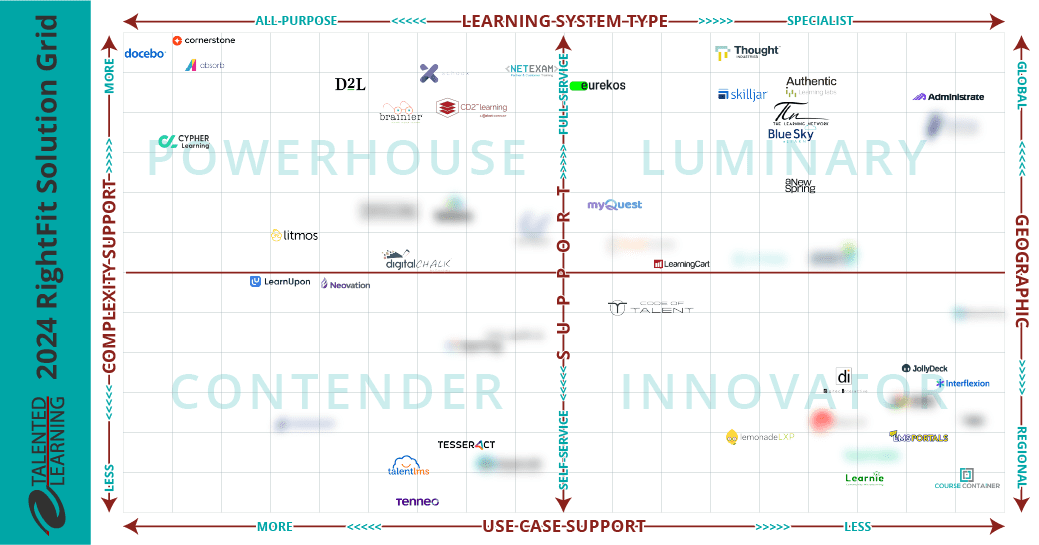

Which LMS is Best for You? New Shortlisting Tool for 2024

How can you find the best learning system for your business? Our LMS shortlisting tool can help. Learn about the 2024 RightFit Solution Grid. Free, reliable guidance based on our independent research

How to Build a Learning-Based Business: Executive Q&A Notes

Building and selling online courses may seem easy, but building a profitable learning-based business is far more complex. Find out what successful leaders say about running this kind of business

The Rewards of Community Building: Customer Ed Nugget 14

What role does community play in your customer relationships? Find out why community building is such a powerful force in customer education on this Customer Ed Nuggets episode

Benefits of Training Content Syndication: Customer Ed Nugget 13

If you educate customers online, why should you consider content syndication? Discover 10 compelling business benefits in this Customer Ed Nuggets episode

Top Marketing Skills to Master: Customer Ed Nugget 12

Successful customer education programs depend on professionals with expertise in multiple disciplines. Which marketing skills lead to the best results?

How to Measure and Improve Partner Training ROI

An educated channel is a successful channel. But how do you know if your educational programs are effective? Learn from an expert how to evaluate partner training ROI

Mistakes in Ongoing Customer Training: Customer Ed Nugget 11

Customer education doesn't stop with onboarding. It pays to invest in ongoing customer training. Learn which mistakes to avoid in this Customer Ed Nuggets episode

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL